Christopher Columbus tall ships race from Boston to Liverpool England by Paul Nixon

Adventure aboard a Tall Ship (1992)

One day while reading a sea history magazine, an advertisement in one of the back pages caught my

attention. A replica 19th century Brigantine ship sailing up from Australia was advertising for crew

members to come join her as part of a sail training adventure. Sailing half way around the world, it would

join a fleet of tall ships and participate in the celebrations of the 500 anniversary of Christopher

Columbus in the USA. Not only that, but this ship the Soren Larsen had been featured in many successful

movies and a BBC series The Onedin Line that I watched in earnest on TV from 1971-1980. As soon as I

got home I got on the phone to Australia. Questions that were asked of me were, “Can I swim.” No.”

“Are you afraid of heights?” “Yes”. Not looking good so far? Eventually when it came down to cash

money I was accepted.

The day I signed aboard in Boston harbor, Prince Philip had arrived to greet the crew and wish us all

every success in winning a Trans Atlantic race with 86 other tall ships. The nautical distance of 3300

miles to Liverpool would take us four weeks to cross. An attractive Australian girl on board by the name

of Jocelyn Forbes took me under her wing; she was a veteran sailor having sailed with this ship since the

beginning a year prior.

I remember so well the thrill on the day when all of the tall ships were led out of Boston Harbour

followed by anything that could pretty well float just to be able to participate on that historical day.

Because of a late supply delivery, the Soren was the last ship to leave the harbor.

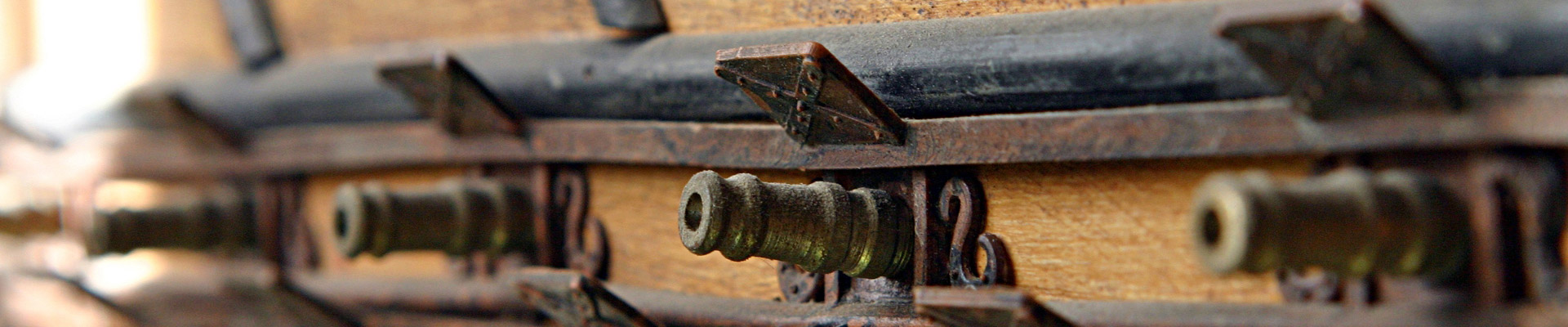

As we finally set out to the cheer of thousands, we were met by the USS Constitution (old iron side); one

of the original of six US frigates with 44 guns built in 1794 and granted its name by President

Washington. Having led the parade of sail out into deep water, she was now returning to her dock. The

big thrill came in passing her; when with her guns run out, she gave us a broadside of her cannon. These

were the same guns that fired on Barbary pirates and English ships back in the day. The pounding

percussion emanates an eardrum rattling boom and a dense cloud of smoke. This gave us all a real sense

of what it felt like to be on the wrong side of her during her heyday.

In heavy fog the next morning we fumbled our way around an unfamiliar deck. Out in deep water it was

impossible to see your hand in front of your face. From all directions horns and ships bells tolled their

warning in the muffled gloom creating an uncanny setting. Suddenly on the third day out of nowhere a

storm came out of the fog and caught the Soren under full canvas. All of a sudden it drove her fast

through building waves. The hull groaned in tune with the wailing cordage. Polished timbers that were

long retired from northern woodlands lamented their age in moans and whines. White water poured over

the bows, deluged the deck, and foamed on the barriers of the decks obstacles. Swelling and billowing

sheets of canvas strained by the power of the gale began to shred and rip. The vessel heeling with the roll

of the ocean, this sudden upheaval caught everyone aboard by surprise. Dishes clashed. Drinks, spilled

and bodies piled upon one other. There were some minor injuries which were quickly attended. I

remember looking up through the hatchway as men scrambled upward into the rigging against a violent

wind to pull down sails clinging to rope, their own clothes ballooning with an effort to pull them from the

rigging into the boiling froth. Safety ropes were quickly wrapped around each of our waists, whether you

were experienced or not , you were needed on deck to assist those in needs. Hauling on wet ropes great

waves and foam crashed over the bow and our heads leaving us constantly waist deep in water. Then a

huge wave dislodged my footing and carried me like a helpless baby the safety lines length halfway along

the deck when the security of the ropes attachment jerked me to a sudden stop. Spitting out seawater I

hauled myself back to my position with the assistance of others. We would have lost men if the crew had

hadn’t secured stout lifelines rigged fore and aft. Our ship pitched and rolled disappearing into deep

troughs and rising again high on a crest only to fall into the next depression. At times the crests ahead

seemed so immense I began to wonder if the ship could even mount them?

Through fog, storm and all the Atlantis had to offer, we found ourselves in the lead guided by an

experienced skipper who took advantage of the gale allowing it to propel us far ahead of the fleet. For the

month that passed within close confinement with 40 other crew members, we created our own unique

world. The ship offered a wonderful venue of teamwork and human encounters, but she also demanded

constant attention, alertness and vigilance. All works were shared responsibilities as they were

continuous. For the first four days I was assigned to galley duty. The galley is a magical hub of activity

that is the social center and heart of the ship; however this can be a challenging affair particularly with

rough seas. With the ship lurching violently it’s no mean feat to get boiling water into coffee and tea pots,

and then there are the second helpings of the watch crew who pass their plates for more stew which turns

your stomach, and all you want to do is throw up. The evening meal too had its challenges as in leaving

the galley you had to negotiate the stairways with loaded trays of boiled potatoes, cooked tuna freshly

caught earlier that day. As I side stepped to the motion of the ship maintaining a balancing act I rejoiced

on my achievement of delivering the food to a cheering crew. The midnight shift (12 to 4 am) or

graveyard shift consists of baking bread for the following day where there is a keen competition on board

to bake the best bread to which each shift has the opportunity to devour one of the loaves while fresh and

hot before retiring for the night. This was done continuously on the voyage where they are served up for

breakfast the following day. It was also here at the time that all of the world’s problems and political

misgivings were resolved.

On the fifth day I was assigned to watch duty. Every four days my shift changed to where I experienced a

full 24 hour rotation. Each watch had a certified officer in charge and on this voyage we are working four

hours on and eight hours off so that if you do the forenoon watch from 0800 to noon, you also do the so

called first watch-2000 to midnight. The passing of time is marked every half hour throughout the day and

night by strokes of the ships bell which is right foreword hanging on the forestay. At the change of each

watch eight bells were struck in four pairs. Back in the day each half hour was measured by a 30 minute

hour glass. It’s a time honored system and hearing its unique tone struck on a ship at sea is as redolent as

the cry of a seabird.

Throughout the remaining part of the voyage I would take to the rigging just to see the open sea high on

the earth’s curve and feel her breath on my face. At night in a small dark cabin shared by three others

with the creaking timbers and the ocean swishing its action just a few inches on the other side of the

wood planking, quickly put everything in perspective. My favorite time for working was the morning

watch from midnight to 0400 and from 0400 to 0800. After midnight when I was alone on bow watch

with each lunge from the ship as her sails pressed her from trough to trough, its pounding impact would

cast white phosphorous spray onto me and the surrounding deck, illuminating its contact with millions of

flickering starlight’s that faded in an instance. In the dark water dolphins and shoals of fish can be seen in

streaks of blue, red and crimson. The effect of the shower light which falls from the shiny scales is very

alluring indeed. In that moment I felt I was in the lead alone on a timeless journey in the middle of an

ocean enchanted by her spell.

Eventually we arrived off the south west coast of Ireland. Of all the places in the world for turbulent

waters, the Atlantic that day became like a mill pond. Curious dolphins arrived, their play slapping the

tranquil surface, its sound echoing in the calmness. 26 miles off the Irish coast a small finch and a

butterfly seek refuge in the rigging. To cross the finish line we had to pass Carransore Point off the coast

of Wexford just 20 miles away. However with no wind we sat there riding the current. In three hours we

gained six miles. On the second night at 3:30 AM just two miles from the finish line I was awakened from

my bunk and told that I was on duty and to go to the helm. I remember in the quiet darkness accompanied

with a gentle breeze and a low keyed conversation with some crew members and my skipper. It was if we

were respecting the solemnity of the ocean, I struggled with the wheel to keep her on course. Another

shift was about to come on with the finish line within eye distance, I soon handed the wheel over to my

replacement. An objection among the crew supported by the skipper intervenes on my behalf saying,”

The Irish man given that we are on off the coast of his homeland should be given the honor of finishing

this race.” By now everyone on board had been awakened and on deck. 4:15 AM I steer the Soren Larsen

to victory, crossing Carransore Point to the applause of all on board. This was quickly followed by hot

toddies and champagne. Heading north up St. Georges Channel the next morning, two pigeons circled

overhead then landed on the main yard arm. Soon, in traditional sailor’s fashion, we sailed into Liverpool

aloft on the yardarms to the welcomed cheers of over 100,000,000 spectators reliving the heyday, the![]()